Discovering the Impossible

Why the founder of Gandeeva decided to take on cancer

Emily Brady |

Lucky accidents. That’s what Sriram Subramaniam attributes everything interesting that has happened in his career to—from landing a job in a government lab to his current role as the founder of Gandeeva, a startup focused on bringing new cancer drugs to market through the cutting-edge technology of cryogenic electron microscopy and AI.

The first lucky accident occurred shortly after Sriram earned his Ph.D. in physical chemistry from Stanford in 1987. Unable to find a job in physics, he switched to biology and landed a postdoctoral fellowship at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) to work with Nobel-prize-winning scientist Gobind Khorana. That led to a position at Johns Hopkins as an assistant professor, where his curiosity led him to study fruit fly vision.

The next lucky accident took Sriram to Cambridge, England, to work with the Nobel-prize-winning structural biologist Richard Henderson. Henderson pioneered electron microscopy—a technique for obtaining high-resolution images using beams of electrons to illuminate specimens. Sriram had no prior experience with electron microscopy, but the National Institutes of Health (NIH) saw something promising in him.

“They hired me as a permanent tenured scientist, making a bet that I would do something interesting,” recalls Sriram.

Over the next 18 years with the NIH, Sriram did many interesting things, including becoming an expert in electron microscopy and cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and helping develop the technology that led him to found Gandeeva.

A major breakthrough

It was during his tenure at the NIH that Sriram’s dream became clear. He wanted to do something thought to be impossible: He wanted to discern protein structures at an atomic resolution without having to crystallize them.

For those unschooled in the intricacies of biochemistry: For the past five decades, the only way to get atomic resolution information out of proteins was through crystallization. That is to take a protein of interest from a cell, crystallize it into a three-dimensional crystal with billions of molecules, and put it in an X-ray beam to get an atomic model of what the protein contained.

But the problem with this method, according to Sriram, is that “most of the interesting proteins don’t crystallize. Due to their dynamic structure, they can’t always be coaxed into the arrangement you need to make a 3D crystal.”

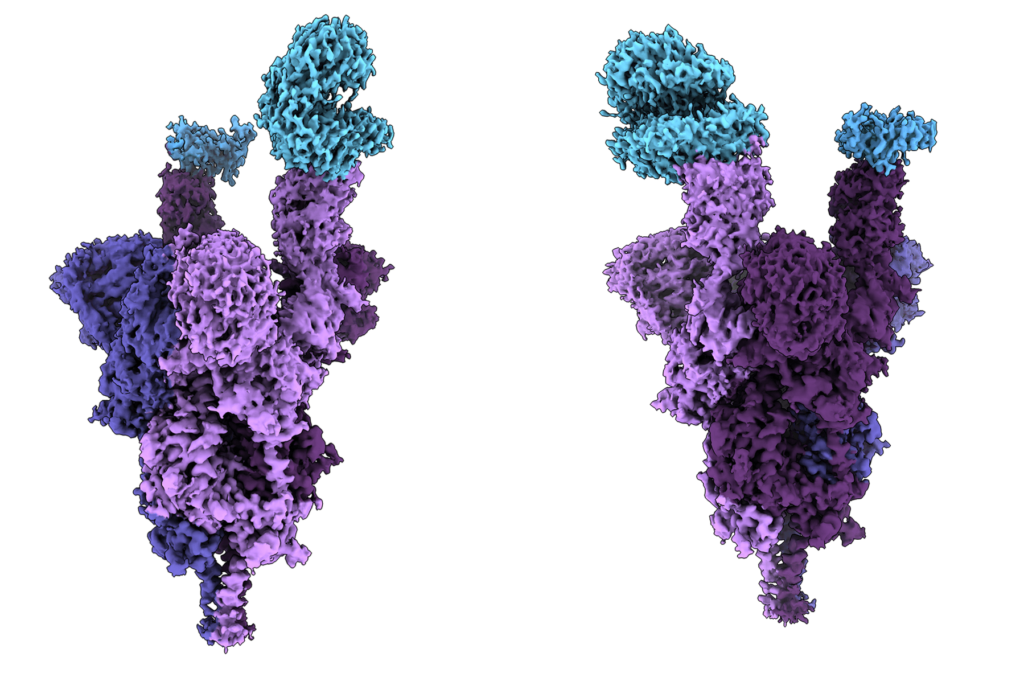

In 2015, Sriram and his team made a major breakthrough. Less a lucky accident and more the result of years of work, they showed for the first time that they could visualize proteins without crystalizing them at an unprecedented level of detail, not much larger than the length of a single bond between two atoms. The following year, Sriram and his team showed that they could not only visualize proteins at this level of detail but also the drug molecules bound to them at the same level.

How did they achieve this level of resolution? Through cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM). Cryo-EM is a technique used in structural biology to study the 3D structures of macromolecules such as proteins. A protein is frozen in a thin layer of ice and placed into an electron microscope. Scientists take millions of images to generate a 3D model of the protein. With these detailed models, scientists can better understand the structure, movement, and function of specific proteins, including the interfaces at which proteins can bind together.

“This was a very important advance,” Sriram says. “Once we got there, it became clear that this could revolutionize drug discovery.”

Customizable arrows

Usually, when you’re a government scientist and make an important discovery, someone else uses your information to build a drug, pharma, or biotech company. Sriram decided to take a different path and lead the charge himself.

In Indian mythology, the Hindu god Brahma created a powerful bow that was eventually given to the hero warrior Arjuna. It came with two quivers and an inexhaustible set of arrows that would take different shapes and forms depending on Arjuna’s target.

The name of this bow was Gandeeva. Sriram chose this same name for the company he founded in a nod to his Indian roots and the symbolism of the arrows.

“We are seeking to develop customized precision medicines to take on numerous targets—one size does not fit all,” he says.

The initial target Sriram has focused Gandeeva’s arrows on is cancer. At the NIH, he’d seen firsthand the hope and desperation of late-stage cancer patients in clinical trials hoping to live just a few months longer. He wanted to develop drugs that not only helped patients live longer but cured their disease.

“We should be able to make drugs quickly, and it should not take seven to 10 years. I wanted to be very close to all the steps in the drug discovery pathway and had a deep desire to do it on a faster timescale,” he says.

On the map

Gandeeva is now a buzzing startup with a 31-strong team based in Vancouver, BC, where Sriram is CEO while simultaneously leading a precision cancer drug discovery program as a professor at the University of British Columbia.

Just around the time Sriram began speaking with investors to finance Gandeeva, a mysterious virus from Wuhan, China, began spreading around the globe. He quickly learned that to continue doing science at the time meant that he and his nascent team needed to quickly learn about coronaviruses and focus on COVID-19.

That work on COVID-19 put Gandeeva on the map. Sriram’s team was the first to post the high-resolution cryo-EM structures of every new variant of concern—from Alpha to Omicron. And in 2021, they produced the world’s first molecular-level imaging of the Omicron variant in just seven days, showing the 37 mutations in its spike proteins and offering researchers a better understanding of how they might neutralize them.

While the pandemic raged, the Gandeeva team kept working and successfully closed their Series A financing round. In the next few months, the team hopes to post their first development cancer drug candidate, a major milestone.

“When we make these compounds and show that they work, that’s how we demonstrate value,” Sriram says.

One thing is for sure: Through hard work and strong science, there will surely be more lucky accidents to come.